Scenes From an Audit

January 22, 2025

How to keep your money safe

March 14, 2025By Clark Troy

Every year around this time Warren Buffett publishes his annual shareholder letter as part of Berkshire Hathaway’s annual report. Its publication becomes an event in the financial media, and rightly so. Buffett writes well, having notably benefited from the “editorial assistance” of Carol Loomis, a distinguished business writer for Fortune for many decades before that publication was subsumed into the same junkyard of history that inevitably takes so many periodicals.

There are those who say that Ms. Loomis is in fact the primary writer of Berkshire’s annual letter, populating it with content provided by Buffett. Who knows what’s true? Loomis and Buffett apparently spoke almost daily and perhaps still do. Loomis shares Buffett’s penchant for exhaustive research, so in some sense one can see her as an extension or component of Buffett's prodigious brain.

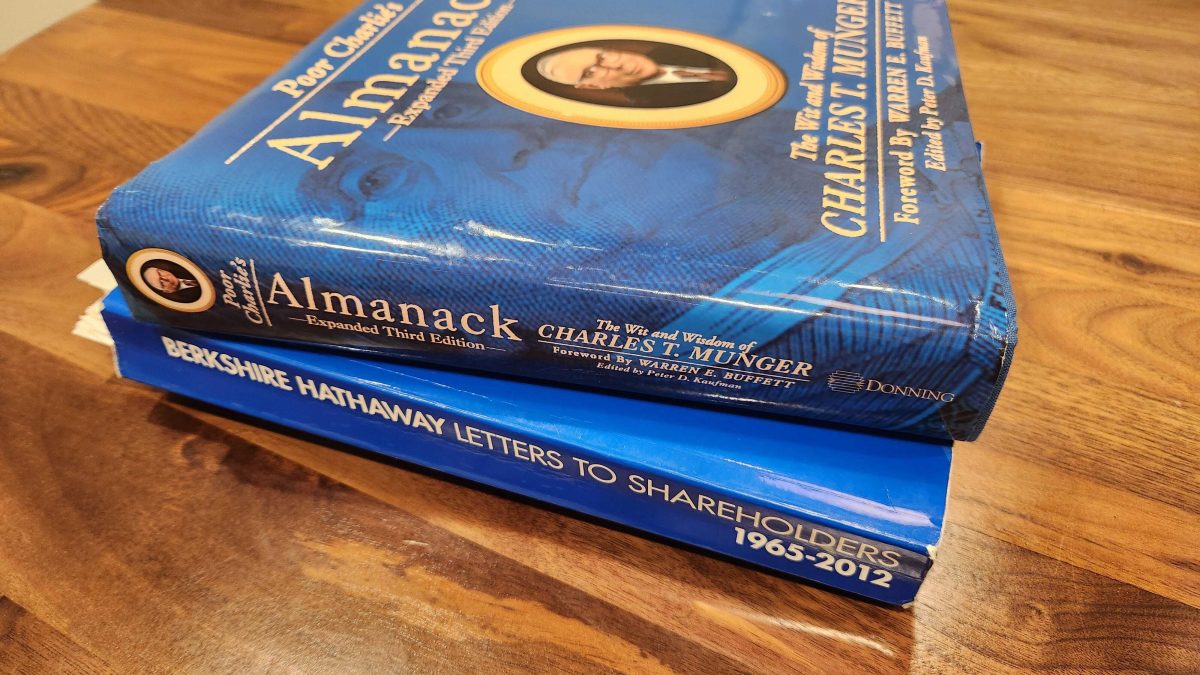

Regardless of who actually wrote them, the Berkshire-Hathaway letters unquestionably warrant reading. Book-length collections of the letters have been published at various junctures, most recently 2014. Pdfs of all the letters from 1977 forward can be found on Berkshire’s website. I highly recommend reading it all.

Some years ago I made it a Sunday project (i.e. I would read one letter each Sunday) to work my way through the letters from 1965 forward. Consumed in this manner, the letters cease to be an annual project and instead assume the character of a continuous evolution, in my case much more an evolution of the reader rather than the writer, though I’m sure some of the latter was going on as well. Depending on the year, the letter may dive deep into granular details of the importance of one accounting practice or another or of some deeply geeky aspect of insurance underwriting, most often the technical detail of the day gets clearly tied back to Berkshire’s earnings or business fundamentals.

Almost always the technical deep-dives are amply leavened with narrative – typically biographical – sketches. The 2024 missive highlights the career of Pete Liegl, founder and CEO of Forest River, an Indiana-based manufacturer of RVs that Berkshire acquired in 2005 but which Pete continued to run till his death last year for a salary – identical to Buffett’s -- of $100k (“I wouldn’t want to be paid more than my boss”) plus a portion of earnings.

But unquestionably the greatest heroine of the Berkshire canon was Rose Blumkin, matriarch of the Nebraska Furniture Mart in Omaha from its founding in 1937 through its acquisition by Berkshire in 1983 until she was forced into retirement at the age of 95 in 1989. At that point in time Blumkin took advantage of the lack of a non-compete clause and founded a carpet wholesaler across the street, which Buffett eventually purchased and folded into her original company within the broader bosom of Berkshire. In the letters Buffett endlessly delighted in extolling Blumkin’s indefatigable energy, including in her later years when the mobility-constrained CEO would zip across the massive floors of her stores on an electronic scooter encouraging her team to keep moving product at low, low prices to provide the greatest value. Then the lady vanishes. Buffett pens no eulogy to Rose Blumkin, perhaps the greatest mystery in all the Berkshire letters. Maybe her family requested it.

This year’s letter foregrounds on page one that Berkshire makes mistakes, sometimes when investing in stocks, sometimes when purchasing businesses outright. But over the years Buffett has been happy to slide over some notable mistakes in silence while “tap-dancing to work,” as he has been fond of saying. For instance, there was the case of Dave Sokol, who had been CEO of Berkshire-owned MidAmerican Energy Holdings and was viewed as a probable heir to the throne at Berkshire but instead left unceremoniously in 2011 after he broke some early-trading laws and was involved in other questionable activities. The letters let that incident pass in resounding silence.

Then there was the time, in 2015, when Berkshire teamed up with Brazilian private equity company 3G Capital to acquire a controlling stake in the packaged foods firm Kraft and merged it with condiment king Heinz, in which they had earlier acquired a controlling interest. This quickly turned disastrous when 3G’s preference for rigid “zero-based budgeting” meant that the new entity, which made its money on brands, after all, didn’t have enough money to do market research and product development and got lapped by consumers’ changing tastes. The company has never really recovered and is now valued at about a third of its peak value, less than half of where it was before the merger. Again, Buffett stayed mum when his reflections might have proved edifying for his readers.

But these are minor objections. Nobody’s perfect, and the Berkshire-Hathaway shareholder letters reward the persistent reader with considerable wisdom in general and often nitty-gritty insight into specific businesses.

But they are far from the crown in the Berkshire-Hathaway canon. This role is reserved for Poor Charlie’s Almanac, a collection of texts attributed to Buffett’s longtime coequal partner Charlie Munger, who shuffled off from this mortal coil a month or so shy of his 100th birthday in late 2023. If Buffett has written little, Munger wrote even less. Poor Charlie’s Almanac, at least the 2019 hardcover edition I own, is an impressive and weighty tome, but much of it consists of commentary by the editor, Peter Kaufman (himself the CEO of a private company); a collection of quotes cribbed from notes from things Charlie said at annual meetings compiled by the famed value investor Whitney Tilson; and pictures with biographical sketches of the wide variety of people Charlie quotes and references. The core of the book is formed by the texts of eleven talks Charlie gave at various events down through the years at commencements, reunions, annual meetings, etc.

But Munger’s texts contain multitudes of observations and reflections and focus much less on investing and economics than on continuous and syncretic learning. Rather than try to summarize or excerpt Munger’s writings my mind instead reaches back to an anecdote about Ludwig Wittgenstein attending a book group discussion of Tolstoi’s Anna Karenina in Vienna in the 1920s. Asked what he thought about the novel, Wittgenstein picked up his copy of it and began reading from the beginning. Like Tolstoi, Munger resists easy summarization. If you are really pressed for time, start with Munger’s last piece, a combination of three talks, one at Caltech, two at Harvard, “The Psychology of Human Misjudgment.” You’ll probably go back and read more.

In the end, neither Buffett nor Munger has really given us a whole lot in terms of text. What they have done is worth reading, but there’s no shortcutting the process. I think the best epigraph to the whole project comes from a quote from Munger about Jim Sinegal, the longtime CEO of Costco, one of Charlie’s largest and longest held investments. Asked why Sinegal had written so little about the secrets to Costco’s success, Munger responded: “He was working.”

Which is what, I suppose, I should get back to doing.

This article originally appeared on Straight Edge Finance. Click here to read more from Clark Troy.